Papacy and Christian Unity

Institution of the Papacy

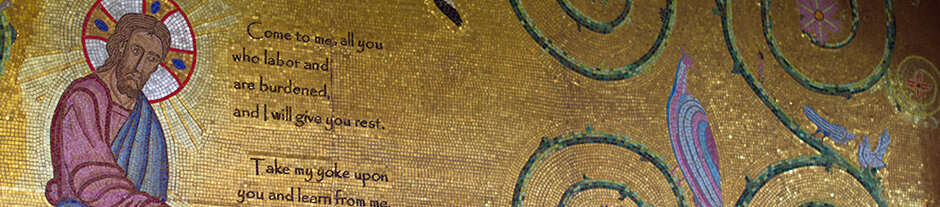

The Pope is the successor of St. Peter, who Jesus called the “rock” on which the Church was to be built and to whom the “keys” of the kingdom of heaven were entrusted. As Vicar of Jesus Christ, the Pope governs the Catholic Church as its supreme head. The Pope, as Bishop of Rome, is the chief pastor and shepherd of the whole Church.

The Scriptures make it clear that Christ chose Peter as head of His Church. Peter was commissioned by Christ to continue his mission and ministry. Peter’s leadership in the early church, after the Ascension of the Lord, is clearly established in the Acts of the Apostles. More than simply establishing a single person as supreme head of the church, Christ instituted a perpetual office of leadership, which is the institution of the papacy. We as Catholics believe that the present Pope follows in apostolic succession in line with the supremacy entrusted to St. Peter. The permanence of the office of chief pastor, first held by Peter, is essential to the very being of the Church.

““The Roman Pontiff, as the successor of Peter, is the perpetual and visible principle and foundation of unity of both the bishops and of the faithful.”

”

The Pope has therefore been established by Christ to be the supreme teacher and ruler of the Church. In fulfilling this office, the Pope is called to protect what is to be believed by all the faithful and to preserve the tradition of faith handed on through the generations.

The Pope is responsible for many things. He teaches on matters of morals and faith, has responsibility for the liturgical life of worship of the Church, is responsible for the canonization of saints, has supreme judicial authority and makes all appointments to the public offices of the church.

Election of a New Pope

After the death (or resignation) of a Pope, the governing of the Church falls to the Sacred College of Cardinals, whose main responsibility becomes the election of a new Pope. The Conclave, which consists of about 120 electors, is the gathering of cardinals for the purpose of selecting a new pope. Only cardinals under the age of 80 can vote. The Conclave takes place in the strictest isolation so as to avoid the possibility of any external influences or interference. The cardinals who are able to vote enter the Sistine Chapel and follow a detailed procedure for the casting of secret ballots. Ballots are cast once during the first day of the Conclave, and then two times a day (at a morning and evening session) until a new pope is elected. Current church law states that one must be a bishop in order to be chosen as Pope, and current practice is that the College of Cardinals will select one of their own number as the new Pope.

Each vote begins with the preparation and distribution of paper ballots by two masters of ceremonies, who are among a handful of non-cardinals allowed into the chapel at the start of the session. Then the names of nine voting cardinals are chosen at random: three to serve as "scrutineers," or voting judges; three to collect the votes of any sick cardinals who remain in their quarters; and three "revisers" who check the work of the scrutineers. On the top half of the rectangular ballot is printed the Latin phrase "Eligo in Summum Pontificem" ("I elect as the most high pontiff"), and the lower half is blank for the writing of the name of the person chosen. After all the non-cardinals have left the chapel, the cardinals fill out their ballots secretly, legibly and fold them twice. Meanwhile, any ballots from sick cardinals are collected and brought back to the chapel. Each cardinal then walks to the altar, holding up his folded ballot so it can be seen, and says aloud: "I call as my witness Christ the Lord who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one who before God I think should be elected." He places his ballot on a plate, or paten, and then slides it into a receptacle, traditionally a large chalice.

When all the ballots have been cast, the first scrutineer shakes the receptacle to mix them. He then transfers the ballots to a new urn, counting them to make sure they correspond to the number of electors. The ballots are read out. Each of the three scrutineers examines each ballot one-by-one, with the last scrutineer calling out the name on the ballot, so all the cardinals can record the tally. The last scrutineer pierces each ballot with a needle through the word "Eligo" and places it on a thread, so they can be secured. After the names have been read out, the votes are counted to see if someone has obtained a two-thirds majority needed for election -- or a simple majority if the rules are changed later in the conclave. The revisers then double-check the work of the scrutineers for possible mistakes. At this point, any handwritten notes made by the cardinals during the vote are collected for burning with the ballots. If the first vote of the morning or evening session is inconclusive, a second vote normally follows immediately, and the ballots from both votes are burned together at the end.

When a pope is elected, the ballots are burned immediately. By tradition, the ballots are burned dry -- or with chemical additives -- to produce white smoke when a pope has been elected; they are burned with damp straw or other chemicals to produce black smoke when no pope has been elected yet. The most notable change introduced by Pope John Paul II into the voting process was to increase the opportunity of electing a pope by simple majority instead of two-thirds majority, after a series of ballots. The two-thirds majority rule holds in the first phase of the conclave: three days of voting, then a pause of up to one day, followed by seven ballots and a pause, then seven more ballots and a pause, and seven more ballots. At that point -- about 12 or 13 days into the conclave -- the cardinals can decide to move to a simple majority for papal election and can limit the voting to the top two vote-getters. In earlier conclaves, switching to a simple majority required approval of two-thirds of the cardinals, but now that decision can be made by simple majority, too.

Once a new Pope has been elected, he chooses a name and receives the obedience of the Cardinals. The senior Cardinal Deacon announces the name of the new Pope, who then gives his blessing to the people, the city, the Church, and the world. A new Bishop of Rome and universal Pastor of the Church has been chosen!

Papal Infallibility

Infallibility does not mean that the Pope is perfect or never makes mistakes. What it does mean is that when he teaches on matters of faith and morals in his official capacity as chief shepherd of the Catholic Church those teachings are free from error by virtue of the Holy Spirit who "will lead you into all truth" (John 16:13; see also John 14:16-17, 26 and Luke 10:16). The Pope speaks infallibly when the following conditions are met:

As the visible head of the universal Church

To all Catholics

On a matter of faith or morals

Intending to use his full authority in an un-changeable decision

The Pope speaking infallibly is not a common occurrence and differs from a regular Papal address or homily. The Pope’s intent to use his full authority in an un-changeable decision is always clearly stated and known. Infallibility means that the Church that Christ founded is, by a special Divine assistance, preserved from liability to error in her definitive teachings regarding matters of faith and morals. "The Roman Pontiff, head of the college of bishops, enjoys this infallibility in virtue of his office, when, as supreme pastor and teacher of all the faithful - who confirms his brethren in the faith - he proclaims by a definitive act a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals. . . . The infallibility promised to the Church is also present in the body of bishops when, together with Peter's successor, they exercise the supreme Magisterium, above all in an Ecumenical Council." [Catechism of the Catholic Church no. 891]